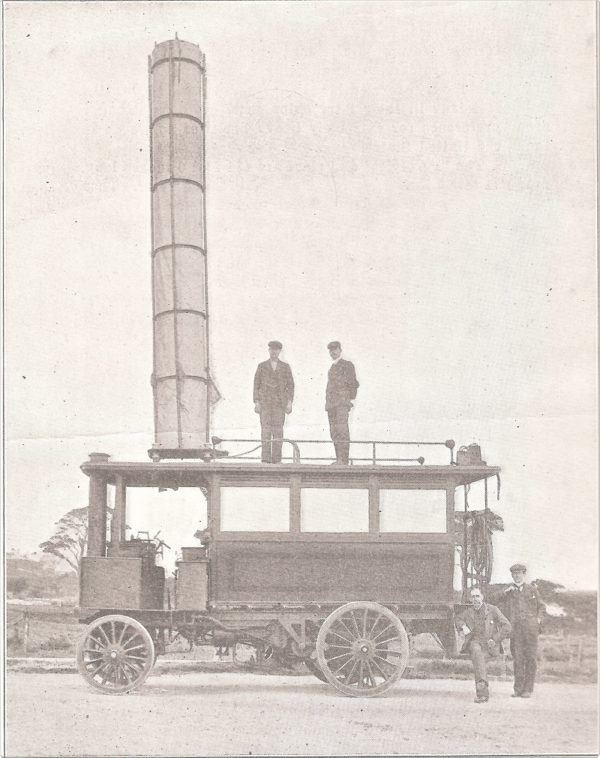

The 80th anniversary of the death of Guglielmo Marconi will be on 20th July next week, so we wanted to celebrate his many contributions to communication with this image – coincidentally from the 20th July 1901 issue of Scientific American.

The vehicle is a Thornycroft steam lorry, described in the accompanying article by the English Correspondent as being ‘now so much used in England for heavy road traffic.’

The lorry was clearly chosen for Mr Marconi’s purposes: it had a carrying capacity of 5 tons, and was said to be capable of a speed from twelve to fourteen miles per hour with a full load. The rear part of the lorry was fitted out as an operating room, containing instruments and electric batteries, and on the roof was placed the all-important cylinder aerial.

This type of aerial was developed for the British Army after significant problems encountered in South Africa during the early stages of the Boer War. The War Department was already using Marconi wireless telegraphy to communicate to the coast the arrival of various transports at points inland. But when asked to travel to the front, the operators found no trees to which they could attach their aerial wires. The military kite provided by Major Baden-Powell (later to be founder of the scout movement) was rejected by Marconi for its ‘liability to fall to the ground.’ Really? You don’t say. So the whole system was abandoned.

But Marconi had already been experimenting with huge cylinders to act as receivers in lieu of high wires, and now devised the solution in our picture, with the cylindrical aerial laid down flat on the roof of the lorry when being transported, and erected as we show here when required for operation. The cylinder was about twenty-five feet in height, and we can see the points for transmission of signals at the top, and the wires down the cylinder, taking the signals to and from the instruments in the operating room.

Marconi and the British Army selected this steam lorry for its strength of construction, which made it ideally suited for work over rough ground. The system was also able to transmit and receive signals while moving. At the time of this article the British Army was conducting ‘exacting trials’ to prove the system’s efficiency. The maximum transmission distance was at this point 20 miles, suitable for many general military purposes, but Marconi’s experiments and developments were continuing.

This communication distance from a mobile transmitter may seem very small, until we remember that Marconi had not yet transmitted radio signals much further than 60 miles, from an ocean liner to a coastal station. But development was rapid: in December 1902 Marconi made the first transatlantic radio transmission. And in a parallel development, Thornycroft built their first petrol-engined vehicle in the same year.

Leave a Comment